Weddell Sea on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Weddell Sea is part of the

In 1823, British sailor James Weddell discovered the Weddell Sea.

In 1823, British sailor James Weddell discovered the Weddell Sea.

Foraminifera of the Weddell Sea bottom

an image gallery of hundreds of specimens of deep-sea Foraminifera from depths around 4,400 metres {{Coord, 75, S, 45, W, region:AQ_type:waterbody_scale:20000000, display=title British Antarctic Territory Chilean Antarctic Territory Seas of the Southern Ocean Argentine Antarctica Filchner-Ronne Ice Shelf Antarctic region Back-arc basins

Southern Ocean

The Southern Ocean, also known as the Antarctic Ocean, comprises the southernmost waters of the World Ocean, generally taken to be south of 60° S latitude and encircling Antarctica. With a size of , it is regarded as the second-small ...

and contains the Weddell Gyre

The Weddell Gyre is one of the two gyres that exist within the Southern Ocean. The gyre is formed by interactions between the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) and the Antarctic Continental Shelf. The gyre is located in the Weddell Sea, and r ...

. Its land boundaries are defined by the bay formed from the coasts of Coats Land

Coats Land is a region in Antarctica which lies westward of Queen Maud Land and forms the eastern shore of the Weddell Sea, extending in a general northeast–southwest direction between 20°00′W and 36°00′W. The northeast part was discove ...

and the Antarctic Peninsula

The Antarctic Peninsula, known as O'Higgins Land in Chile and Tierra de San Martín in Argentina, and originally as Graham Land in the United Kingdom and the Palmer Peninsula in the United States, is the northernmost part of mainland Antarctic ...

. The easternmost point is Cape Norvegia at Princess Martha Coast

Princess Martha Coast ( no, Kronprinsesse Märtha Kyst) is that portion of the coast of Queen Maud Land lying between 05° E and the terminus of Stancomb-Wills Glacier, at 20° W. The entire coastline is bounded by ice shelves with ice cliffs ...

, Queen Maud Land

Queen Maud Land ( no, Dronning Maud Land) is a roughly region of Antarctica claimed by Norway as a dependent territory. It borders the claimed British Antarctic Territory 20° west and the Australian Antarctic Territory 45° east. In addit ...

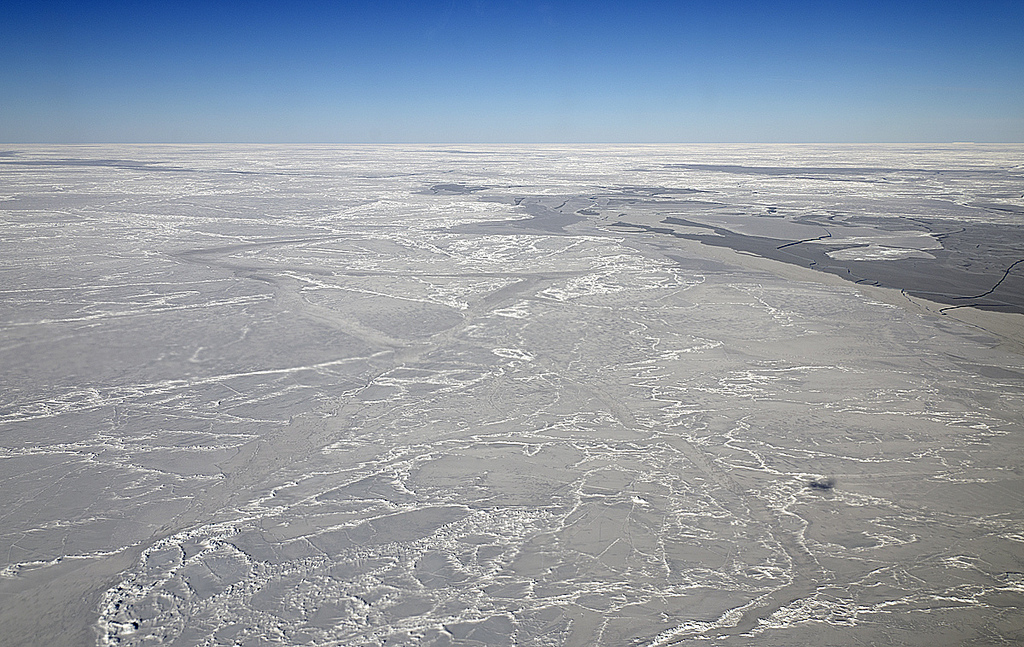

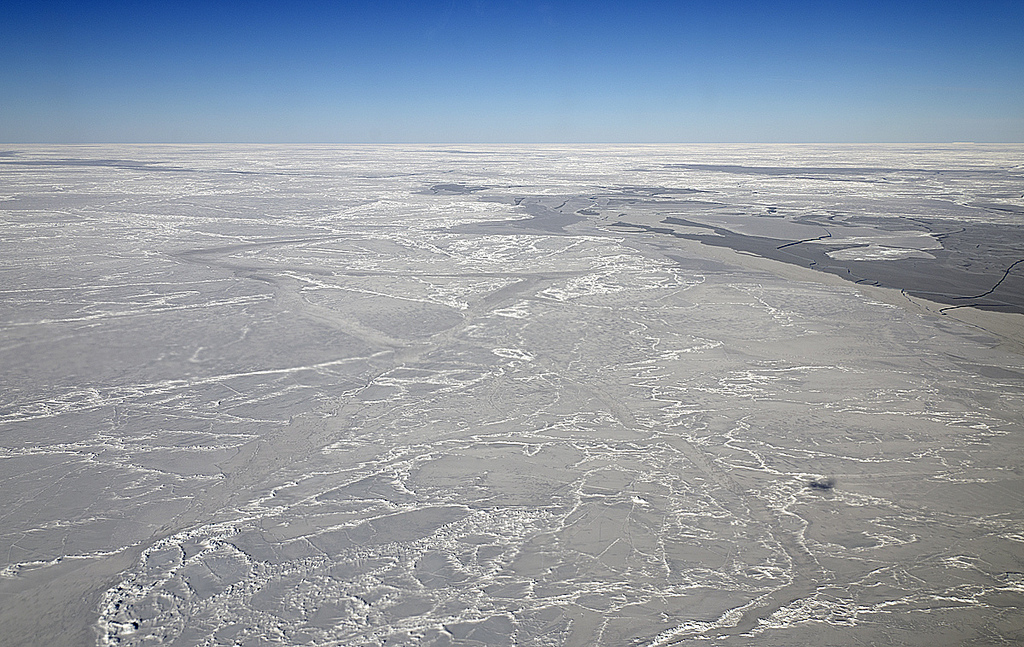

. To the east of Cape Norvegia is the King Haakon VII Sea. Much of the southern part of the sea is covered by a permanent, massive ice shelf

An ice shelf is a large floating platform of ice that forms where a glacier or ice sheet flows down to a coastline and onto the ocean surface. Ice shelves are only found in Antarctica, Greenland, Northern Canada, and the Russian Arctic. The ...

field, the Filchner-Ronne Ice Shelf.

The sea is contained within the two overlapping Antarctic

The Antarctic ( or , American English also or ; commonly ) is a polar region around Earth's South Pole, opposite the Arctic region around the North Pole. The Antarctic comprises the continent of Antarctica, the Kerguelen Plateau and other ...

territorial claims of Argentine Antarctica

Argentine Antarctica ( es, Antártida Argentina or Sector Antártico Argentino) is an area of Antarctica claimed by Argentina as part of its national territory. It consists of the Antarctic Peninsula and a triangular section extending to the ...

, the British Antarctic Territory

The British Antarctic Territory (BAT) is a sector of Antarctica claimed by the United Kingdom as one of its 14 British Overseas Territories, of which it is by far the largest by area. It comprises the region south of 60°S latitude and between ...

, and also resides partially within the Antarctic Chilean Territory. At its widest the sea is around across, and its area is around .

Various ice shelves, including the Filchner-Ronne Ice Shelf, fringe the Weddell sea. Some of the ice shelves on the east side of the Antarctic Peninsula

The Antarctic Peninsula, known as O'Higgins Land in Chile and Tierra de San Martín in Argentina, and originally as Graham Land in the United Kingdom and the Palmer Peninsula in the United States, is the northernmost part of mainland Antarctic ...

, which formerly covered roughly of the Weddell Sea, had completely disappeared by 2002. The Weddell Sea has been deemed by scientists to have the clearest water of any sea. Researchers from the Alfred Wegener Institute

The Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (German: ''Alfred-Wegener-Institut, Helmholtz-Zentrum für Polar- und Meeresforschung'') is located in Bremerhaven, Germany, and a member of the Helmholtz Association o ...

, on finding a Secchi disc

The Secchi disk (or Secchi disc), as created in 1865 by Angelo Secchi, is a plain white, circular disk in diameter used to measure water transparency or turbidity in bodies of water. The disc is mounted on a pole or line, and lowered slowly down ...

visible at a depth of on , ascertained that the clarity corresponded to that of distilled water.

In his 1950 book ''The White Continent'', historian Thomas R. Henry writes: "The Weddell Sea is, according to the testimony of all who have sailed through its berg-filled waters, the most treacherous and dismal region on earth. The Ross Sea

The Ross Sea is a deep bay of the Southern Ocean in Antarctica, between Victoria Land and Marie Byrd Land and within the Ross Embayment, and is the southernmost sea on Earth. It derives its name from the British explorer James Clark Ross who vi ...

is relatively peaceful, predictable, and safe." He continues for an entire chapter, relating myths of the green-haired merman

Mermen, the male counterparts of the mythical female mermaids, are legendary creatures, which are male human from the waist up and fish-like from the waist down, but may assume normal human shape. Sometimes they are described as hideous and other ...

sighted in the sea's icy waters, the inability of crews to navigate a path to the coast until 1949, and treacherous "flash freezes" that left ships, such as Ernest Shackleton

Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton (15 February 1874 – 5 January 1922) was an Anglo-Irish Antarctic explorer who led three British expeditions to the Antarctic. He was one of the principal figures of the period known as the Heroic Age of ...

's , at the mercy of the ice floe

An ice floe () is a large pack of floating ice often defined as a flat piece at least 20 m across at its widest point, and up to more than 10 km across. Drift ice is a floating field of sea ice composed of several ice floes. They may cau ...

s.

Etymology

The sea is named after the Scottish sailorJames Weddell

James Weddell (24 August 1787 – 9 September 1834) was a British sailor, navigator and seal hunter who in February 1823 sailed to latitude of 74° 15′ S—a record 7.69 degrees or 532 statute miles south of the Antarc ...

, who entered the sea in 1823 and originally named it after King George IV

George IV (George Augustus Frederick; 12 August 1762 – 26 June 1830) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from the death of his father, King George III, on 29 January 1820, until his own death ten y ...

; it was renamed in Weddell's honour in 1900. Also in 1823, the American sealing captain Benjamin Morrell claimed to have seen land some 10–12° east of the sea's actual eastern boundary. He called this New South Greenland

New South Greenland, sometimes known as Morrell's Land, was an appearance of land recorded by the American captain Benjamin Morrell of the schooner ''Wasp'' in , during a sealing and exploration voyage in the Weddell Sea area of Antarctica. Mor ...

, but its existence was disproved when the sea was more fully explored in the early 20th century. Weddell got as far south as 74°S; the furthest southern penetration since Weddell but before the modern era was made by William Speirs Bruce

William Speirs Bruce (1 August 1867 – 28 October 1921) was a British Natural history, naturalist, polar region, polar scientist and Oceanography, oceanographer who organized and led the Scottish National Antarctic Expedition (SNAE, 1902–04) ...

in 1903.

The Weddell Sea is an important area of deep water mass formation through cabbeling

Cabbeling is when two separate water parcels mix to form a third which sinks below both parents. The combined water parcel is denser than the original two water parcels.

The two parent water parcels may have the same density, but they have diff ...

, the main driving force of the thermohaline circulation

Thermohaline circulation (THC) is a part of the large-scale ocean circulation that is driven by global density gradients created by surface heat and freshwater fluxes. The adjective ''thermohaline'' derives from '' thermo-'' referring to temper ...

. Deepwater masses are also formed through cabbeling in the North Atlantic and are caused by differences in temperature and salinity of the water. In the Weddell sea, this is brought about mainly by brine exclusion and wind cooling.

History

In 1823, British sailor James Weddell discovered the Weddell Sea.

In 1823, British sailor James Weddell discovered the Weddell Sea. Otto Nordenskiöld

Otto is a masculine German given name and a surname. It originates as an Old High German short form (variants ''Audo'', ''Odo'', ''Udo'') of Germanic names beginning in ''aud-'', an element meaning "wealth, prosperity".

The name is recorded fro ...

, leader of the 1901–1904 Swedish Antarctic Expedition

The Swedish Antarctic Expedition of 1901–1903 was a scientific expedition led by Otto Nordenskjöld and Carl Anton Larsen. It was the first Swedish endeavour to Antarctica in the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

Background

Otto Nordensk ...

, spent a winter at Snow Hill with a team of four men when the relief ship became beset in ice and was finally crushed. The crew managed to reach Paulet Island

Paulet Island is a circular island about in diameter, lying south-east of Dundee Island, off the north-eastern end of the Antarctic Peninsula. Because of its large penguin colony, it is a popular destination for sightseeing tours.

Descripti ...

where they wintered in a primitive hut. Nordenskiöld and the others finally were picked up by the Argentine Navy

The Argentine Navy (ARA; es, Armada de la República Argentina). This forms the basis for the navy's ship prefix "ARA". is the navy of Argentina. It is one of the three branches of the Armed Forces of the Argentine Republic, together with the ...

at Hope Bay

Hope Bay (Spanish: ''Bahía Esperanza'') on Trinity Peninsula, is long and wide, indenting the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula and opening on Antarctic Sound. It is the site of the Argentinian Antarctic settlement Esperanza Base, established i ...

. All but one survived.

The Antarctic Sound

The Antarctic Sound is a body of water about long and from wide, separating the Joinville Island group from the northeast end of the Antarctic Peninsula. The sound was named by the Swedish Antarctic Expedition under Otto Nordenskjöld for the e ...

is named after the expedition ship of Otto Nordenskiöld. The sound that separates the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula from Dundee Island

Dundee Island is an ice-covered island lying east of the northeastern tip of Antarctic Peninsula and south of Joinville Island. It is named after the city of Dundee in Scotland.

The Petrel Base is a scientific station in Antarctica belonging t ...

is also named "Iceberg Alley", because of the huge icebergs that are often seen here. Snowhill Island, located east of the Antarctic Peninsula. It is almost completely snow-capped, hence its name. Swedish Antarctic Expedition under Otto Nordenskiöld built a cabin on the island in 1902, where Nordenskiöld and three members of the expedition had to spend two winters.

In 1915, Ernest Shackleton

Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton (15 February 1874 – 5 January 1922) was an Anglo-Irish Antarctic explorer who led three British expeditions to the Antarctic. He was one of the principal figures of the period known as the Heroic Age of ...

's ship, , got trapped and was crushed by ice in this sea. After 15 months on the pack-ice Shackleton and his men managed to reach Elephant Island

Elephant Island is an ice-covered, mountainous island off the coast of Antarctica in the outer reaches of the South Shetland Islands, in the Southern Ocean. The island is situated north-northeast of the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, west-so ...

and safely returned. In March 2022, it was announced that the well-preserved wreck of the ''Endurance'' had been discovered from its anticipated location, at a depth of .

Geology

As with other neighboring parts of Antarctica, the Weddell Sea shares a common geological history with southernmostSouth America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the southe ...

. In southern Patagonia

Patagonia () refers to a geographical region that encompasses the southern end of South America, governed by Argentina and Chile. The region comprises the southern section of the Andes Mountains with lakes, fjords, temperate rainforests, and gl ...

at the onset of the Andean orogeny

The Andean orogeny ( es, Orogenia andina) is an ongoing process of orogeny that began in the Early Jurassic and is responsible for the rise of the Andes mountains. The orogeny is driven by a reactivation of a long-lived subduction system along ...

in the Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately Mya. The J ...

extensional tectonics

Extensional tectonics is concerned with the structures formed by, and the tectonic processes associated with, the stretching of a planetary body's crust or lithosphere.

Deformation styles

The types of structure and the geometries formed depend on ...

created the Rocas Verdes Basin, a back-arc basin

A back-arc basin is a type of geologic basin, found at some convergent plate boundaries. Presently all back-arc basins are submarine features associated with island arcs and subduction zones, with many found in the western Pacific Ocean. Most of ...

whose surviving southeastward extension forms the Weddell Sea. In the Late Cretaceous

The Late Cretaceous (100.5–66 Ma) is the younger of two epochs into which the Cretaceous Period is divided in the geologic time scale. Rock strata from this epoch form the Upper Cretaceous Series. The Cretaceous is named after ''creta'', the ...

the tectonic regime of Rocas Verdes Basin changed leading to its transformation into a compressional foreland basin

A foreland basin is a structural basin that develops adjacent and parallel to a mountain belt. Foreland basins form because the immense mass created by crustal thickening associated with the evolution of a mountain belt causes the lithospher ...

– the Magallanes Basin

The Magallanes Basin or Austral Basin is a major sedimentary basin in southern Patagonia. The basin covers a surface of about and has a NNW-SSE oriented shape. The basin is bounded to the west by the Andes mountains and is separated from the Malv ...

– in the Cenozoic

The Cenozoic ( ; ) is Earth's current geological era, representing the last 66million years of Earth's history. It is characterised by the dominance of mammals, birds and flowering plants, a cooling and drying climate, and the current configura ...

. While this happened in South America the Weddell Sea part of the basin escaped compressional tectonics and remained an oceanic basin.

Oceanography

The Weddell Sea is one of few locations in theWorld Ocean

The ocean (also the sea or the world ocean) is the body of salt water that covers approximately 70.8% of the surface of Earth and contains 97% of Earth's water. An ocean can also refer to any of the large bodies of water into which the worl ...

where deep and bottom water masses are formed to contribute to the global thermohaline circulation

Thermohaline circulation (THC) is a part of the large-scale ocean circulation that is driven by global density gradients created by surface heat and freshwater fluxes. The adjective ''thermohaline'' derives from '' thermo-'' referring to temper ...

which has been warming slowly over the last decade. The characteristics of exported water masses result from complex interactions between surface forcing, significantly modified by sea ice processes, ocean dynamics at the continental shelf break, and slope and sub-ice shelf water mass transformation.

Circulation in the western Weddell Sea is dominated by a northward flowing current. This northward current is the western section of a primarily wind-driven, cyclonic gyre called the Weddell Gyre

The Weddell Gyre is one of the two gyres that exist within the Southern Ocean. The gyre is formed by interactions between the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) and the Antarctic Continental Shelf. The gyre is located in the Weddell Sea, and r ...

. This northward flow serves as the primary force of departure of water from the Weddell Sea, a major site of ocean water modification and deep water formation, to the remainder of the World Ocean. The Weddell Gyre is a cold, low salinity surface layer separated by a thin, weak pycnocline

A pycnocline is the Cline (hydrology), cline or layer where the density gradient () is greatest within a body of water. An ocean current is generated by the forces such as breaking waves, temperature and salinity differences, wind, Coriolis effec ...

from a thick layer of relatively warm and salty water referred to as Weddell Deep Water (WDW), and a cold bottom layer.

Circulation in the Weddell Sea has proven difficult to quantify. Geopotential surface heights above the 1000 dB level, computed using historical data, show only very weak surface currents. Similar computations carried out using more closely spaced data also showed small currents. Closure of the gyre circulation was assumed to be driven by Sverdrup transport

The Sverdrup balance, or Sverdrup relation, is a theoretical relationship between the wind stress exerted on the surface of the open ocean and the vertically integrated meridional (north-south) transport of ocean water.

History

Aside from the ...

. The Weddell Sea is a major site for deep water formation.

Thus, in addition to a wind-driven gyre component of the boundary current, a deeper circulation whose dynamics and transports reflect an input of dense water in the southern and southwestern Weddell Sea are expected. Available data does not lend to the quantification of the volume transports associated with this western boundary region, or to the determination of deep convective circulation along the western boundary.

Climate

The predominance of strong surface winds parallel to the narrow and tall mountain range of the Antarctic Peninsula is a remarkable feature of weather and climate in the area of the western Weddell Sea. The winds carry cold air toward lower latitudes and turn into southwesterlies farther north. These winds are of interest not only because of their effect on the temperature regime east of the peninsula but also because they force the drift of ice northeastward into the South Atlantic Ocean as the last branch of the clockwise circulation in the lower layers of the atmosphere along the coasts of the Weddell Sea. The sharp contrast between the wind, temperature, and ice conditions of the two sides of the Antarctic Peninsula has been well known for many years. Strong surface winds directed equatorward along the east side of the Antarctic Peninsula can appear in two different types of synoptic-meteorological situations: an intense cyclone over the central Weddell Sea, a broad east to west flow of stable cold air in the lowest 500-to-1000-metre layer of the atmosphere over the central and/or southern Weddell Sea toward the peninsula. These conditions lead to cold air piling up on the east edge of the mountains. This process leads to the formation of a high-pressure ridge over the peninsula (mainly east of the peak) and, therefore, a deflection of the originally westward current of air to the right, along the mountain wall.Ecology

The Weddell Sea is abundant with whales and seals. Characteristic fauna of the sea include theWeddell seal

The Weddell seal (''Leptonychotes weddellii'') is a relatively large and abundant true seal with a circumpolar distribution surrounding Antarctica. The Weddell seal was discovered and named in the 1820s during expeditions led by British sealing ...

and killer whales

The orca or killer whale (''Orcinus orca'') is a toothed whale belonging to the oceanic dolphin family, of which it is the largest member. It is the only extant species in the genus ''Orcinus'' and is recognizable by its black-and-white pat ...

, humpback whales

The humpback whale (''Megaptera novaeangliae'') is a species of baleen whale. It is a rorqual (a member of the family Balaenopteridae) and is the only species in the genus ''Megaptera''. Adults range in length from and weigh up to . The hump ...

, minke whales

The minke whale (), or lesser rorqual, is a species complex of baleen whale. The two species of minke whale are the common (or northern) minke whale and the Antarctic (or southern) minke whale. The minke whale was first described by the Danish na ...

, leopard seals, and crabeater seal

The crabeater seal (''Lobodon carcinophaga''), also known as the krill-eater seal, is a true seal with a circumpolar distribution around the coast of Antarctica. They are medium- to large-sized (over 2 m in length), relatively slender and pale-c ...

s are frequently seen during Weddell Sea voyages.

The Adélie penguin

The Adélie penguin (''Pygoscelis adeliae'') is a species of penguin common along the entire coast of the Antarctic continent, which is the only place where it is found. It is the most widespread penguin species, and, along with the emperor p ...

is the dominant penguin species in this remote area because of their adaptation to the harsh environment. A colony of more than 100,000 pairs of Adélies can be found on volcanic Paulet Island

Paulet Island is a circular island about in diameter, lying south-east of Dundee Island, off the north-eastern end of the Antarctic Peninsula. Because of its large penguin colony, it is a popular destination for sightseeing tours.

Descripti ...

.

Around 1997, the northernmost emperor penguin

The emperor penguin (''Aptenodytes forsteri'') is the tallest and heaviest of all living penguin species and is endemic to Antarctica. The male and female are similar in plumage and size, reaching in length and weighing from . Feathers of th ...

colony was discovered just south of Snowhill Island in the Weddell Sea. As the Weddell Sea is often clogged with heavy pack-ice, strong ice-class vessels equipped with helicopters are required to reach this colony.

In 2021, sponge

Sponges, the members of the phylum Porifera (; meaning 'pore bearer'), are a basal animal clade as a sister of the diploblasts. They are multicellular organisms that have bodies full of pores and channels allowing water to circulate through t ...

s and other unidentified suspension feeders were reported to have been found growing under the Filchner-Ronne Ice Shelf on a boulder at a depth of 1,233 m (872 of which were ice), 260 km from open water.

In February 2021 the Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research

The Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (German: ''Alfred-Wegener-Institut, Helmholtz-Zentrum für Polar- und Meeresforschung'') is located in Bremerhaven, Germany, and a member of the Helmholtz Association o ...

with RV Polarstern

RV ''Polarstern'' (meaning pole star) is a German research icebreaker of the Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research (AWI) in Bremerhaven, Germany. ''Polarstern'' was built by Howaldtswerke-Deutsche Werft in Kiel and Nobiskrug in R ...

, a colony of approximately 60 million Jonah's icefish was found to inhabit an area in the Weddell Sea. It is estimated that the colony covers around 240 square kilometers, with an average of one nest per every three square meters.

Seabed features

References

Notes Bibliography * * * * *External links

*Foraminifera of the Weddell Sea bottom

an image gallery of hundreds of specimens of deep-sea Foraminifera from depths around 4,400 metres {{Coord, 75, S, 45, W, region:AQ_type:waterbody_scale:20000000, display=title British Antarctic Territory Chilean Antarctic Territory Seas of the Southern Ocean Argentine Antarctica Filchner-Ronne Ice Shelf Antarctic region Back-arc basins